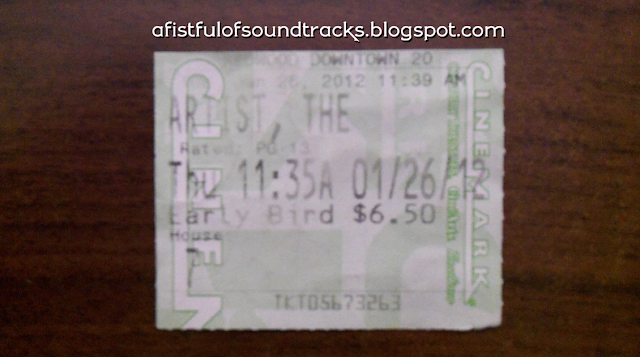

French director Michel Hazanavicius' 2011 silent movie The Artist, the 2012 Best Picture Oscar winner about the end of the silent era in Hollywood, is impossible to dislike. It reteams Jean Dujardin with Hazanavicius' wife Bérénice Bejo--who starred together in OSS 117: Cairo, Nest of Spies, Hazanavicius' amusing 2006 spy spoof about a racist and misogynist '50s French agent--and demonstrates how perfectly cast the two expressive and subtle French stars are as fictional late '20s Hollywood actors who exemplify certain emotive and non-verbal acting styles that were prevalent during The Artist's time period.

In addition to those star turns by Dujardin, who won an Oscar for his role, and the luminous Bejo, a smart and heroic Jack Russell terrier--played by three different dogs--often entertainingly steals the show (the Artist DVD's outtakes of the canine actors missing their cues or ignoring their trainer's instructions are equally entertaining, proving Robert Smigel's theory that much of the funniness of animal actors is due to them not having "any idea what they're part of"). James Cromwell brings his usual material-boosting gravitas to a role that's non-villainous for a change, a stoic and loyal chauffeur who enjoys his work, while, like Dujardin and Bejo, the frequently funny Missi Pyle was born to act in a silent movie, as we see in a way-too-brief role that's clearly an homage to Lina Lamont, Jean Hagen's villainous silent movie star character from Singin' in the Rain.

Another plus is Hazanavicius' attention to the details of late '20s/early '30s Hollywood, with some assistance from his regular composer Ludovic Bource. His Oscar-winning Artist score was influenced by the studio-system-era likes of Max Steiner, Erich Wolfgang Korngold and Bernard Herrmann, whose classic "Scene d'Amour" cue from Vertigo was needle-dropped at one point in The Artist by Hazanavicius, a Hitchcock fan. But the inclusion of a score cue from a well-known 1958 Hitchcock picture during a movie that takes place way before 1958 was too much of an off-putting distraction for some moviegoers, especially Vertigo star Kim Novak, whose bizarre public statement where she angrily referred to the needle drop as "rape" led to a hilarious reaction from Kumail Nanjiani.

Hey Kim Novak, did you know that only 10% of iconic soundtrack theft is actually reported?

— Kumail Nanjiani (@kumailn) January 9, 2012

Guessing Kim Novak's never been raped.

— Kumail Nanjiani (@kumailn) January 9, 2012

It's not as if Hazanavicius soundtracked the movie's angsty climax with Evanescence's "Bring Me to Life," but the purists in the audience who were bent out of shape about the climax would rant and rave as if the director Evanescenced it. Whether or not anachronistic music choices in The Artist or other period pieces like Inglourious Basterds and Public Enemies set off your inner Pierre Bernard, you can't deny how The Artist remarkably never looks like it was made in 2010, thanks mostly to the striking black-and-white visuals of Hazanavicius' regular cinematographer Guillaume Schiffman. At one point, the movie, which Hazanavicius shot entirely in Hollywood, makes beautiful use of the distinctive staircase inside the Bradbury Building, the 122-year-old L.A. filming location most memorably featured in Blade Runner and the 1964 Outer Limits episode "Demon with a Glass Hand."

So like I said before, The Artist is impossible to dislike. But it's hardly the best picture of 2011. As silent movies that were made long after the silent era, Mel Brooks' 1976 farce Silent Movie and Charles Lane's 1989 indie flick Sidewalk Stories are more inventive than The Artist, which, while it does recapture '20s and '30s filmmaking quite well, never really does anything inventive or new with the silent gimmick, other than a memorable nightmare sequence where Dujardin's George Valentin imagines the horrors of being trapped in a new world full of sound. The scenes where George drinks himself into a stupor--over his artistic decline and his inability to adapt to Hollywood's transition from silents to talkies like the box-office successes of Bejo's Peppy Miller--really drag. George's self-pity is about 10 minutes too long. It becomes so repetitive that an enticing-looking two-second clip of Peppy from a fake movie where she stars as a female baseball player ends up being a movie I'd rather watch instead of the actual movie surrounding it.

No comments:

Post a Comment